As part of our Vancouver Island Masonic History Project, with its sections on Vancouver Island Cemeteries – Masonic Interments and Deceased Brethren, here is a page on Frederick James Bailey, a member of United Service Lodge No. 24, who is buried in the Naval & Veterans Cemetery, Esquimalt, B.C.

Frederick James Bailey (died 27 June 1903) was a member of United Service Lodge No. 24 in Victoria. He worked as a Storesman at H.M. Dockyard at Canadian Forces Base Esquimalt.

On 27 June 1903 he was murdered at the Store House of H.M. Dockyard by Albert Frith, one of his subordinates in the Stores Department. The murder of Frederick James Bailey and the subsequent trial, conviction and execution of Albert Frith were considered sensational events in Victoria at the time.

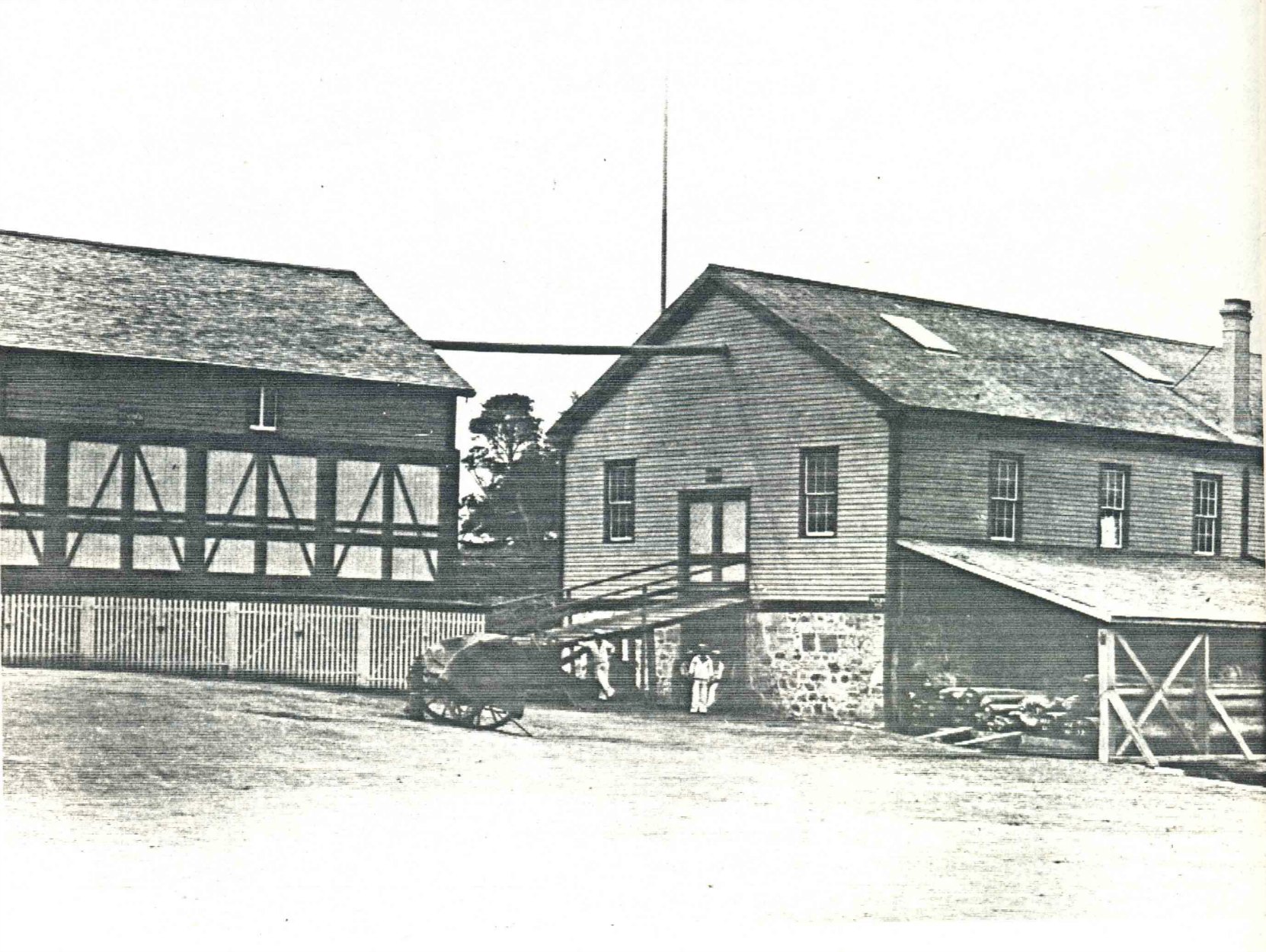

The CFB Esquimalt Naval & Military Museum has informed us that the original Store House/Sail Loft is no longer extant. A newer building has been built on the original Store House/Sail Loft foundations but the newer building does not resemble the original building. Here is a photo of the original building as it probably would have appeared in 1903.

Here is a link to a BC Archives photograph from November 1889 of the interior of the building where Frederick James Bailey was shot: BC Archives photo E-02556 – November 1889

Frederick James Bailey is buried in the Naval and Veterans Cemetery in Esquimalt. Alfred Frith is buried in Ross Bay Cemetery, Victoria.

Here is a brief biography of Frederick James Bailey along with coverage of his murder and the trial and execution of his killer, Alfred Frith, taken from newspaper reports of the day:

“Murder At Esquimalt

——-

Frederick James Bailey Shot and Killed by Alfred J.H. Frith

——-

Was Murdered by Subordinate In Store House at the Naval Yard

——-

Murderer Has Been Arrested and Has Made a Confession To Police

——-

Frederick James Bailey, first-class naval storekeeper at the Royal Navy Yard at Esquimalt, was murdered at 8 o’clock yesterday morning in the oil store room of the sail loft, by Alfred James Henry Frith, a storeman in the Naval Yard, who has been working with the murdered man for nine years, and for the last year as a subordinate. Frith has been arrested by Constable Campbell of the provincial police, and has made a confession of his crime, which he alleges was committed in self defence. He is confined at the provincial jail charged with murder.

There was no witness to the tragedy which horrified the naval village, when some time afterward the body of the murdered storekeeper was found, lying face downward in a pool of blood, which trickled from the wound in the back and front of the head, for the bullet had gone through the head from the back. No one saw the two men as they stood facing each other, discussing the differences that came between them as a result of the discharge of Frith, who was the leave the employ of the yard and the house of the government, within three weeks. Alone, locked in the quiet store-room, Frith had accused Bailey of undermining and – according to the confession of Frith, the only living witness of what took place – Bailey replied warmly and picked up a barrel stave. Then came the tragedy. Frith had whipped a revolver from his pocket and sent Bailey sprawling forward on his face – dead.

Then the murderer locked the [illegible] and leaving his victim cold in death in that ghastly heap among the stores, he went down to the little naval dock, where the big shear leggs stand over the harbor front, and took the weapon which had robbed one man of his life and a family of its head, and placed another man, and a head of a family, in the shadow of the gallows. He hurled the weapon thirty feet or more into the harbor, and the walked from the Naval Yard.

Provincial Constable Dan Campbell met Frith as he came from the yard after committing the murder, and the murderer, smiling, and without any sign to betray the fact that he had just left the victim of his revolver lying dead in the storehouse nearby, asked the constable where he was going, and receiving the reply that the officer was bound to the city, he said:

“You’d better stay around here, Dan; there may be something interesting doing.”

The officer went on to the car, when Frith called him back, and said: “Well, I might as well tell you now.”

“Yes,” replied the officer, “if you’ve got anything to tell me, you’d better, for I’ve got to get to town to attend court.” Meanwhile, the car was waiting, with the conductor impatiently ringing the bell. The constable went to board the car, when Frith said:

“Dan, I’ve killed Bailey! ‘Twas in self-defence.”

The constable, almost incredible, asked him where the body was – having left the car, to stay and investigate. Frith replied, “You’ll find out later on.” The constable, who had known the murderer for some time, found it hard credit his statements, and said: “This isn’t true, is it?” You must be crazy to make such a remark.” Frith replied, “It’s true enough.”

Frith then went off to his house for breakfast, declining to answer any inquiries as to where the body was. Before he went, he asked the constable to come up to his house after breakfast.

Constable Campbell then went to the telephone and asked at the office of the Naval Yard if Bailey was missing. The office staff replied that Bailey was not – that he was at work. The officer then went to the Naval Yard to look for Bailey. He found the Chinese who helped Bailey standing outside the warehouse at which Bailey was generally found, and when the officer asked him when he had last seen Bailey, the Chinese said he had not seen him since 7:30 a.m. He didn’t know where he was for he had not come back.

Constable Campbell then broke open the warehouse, which was locked, and he searched it thoroughly, but failed to find any trace of the murdered man. He then went to report to Superintendent Hussey, having notified the sergeant of marines as he went, and the sergeant of marines began a search of the buildings of the yard for the missing man. When the officer reported to Superintendent Hussey he was instructed to arrest Frith.

Meanwhile Frith had breakfasted with his family at the house he been ordered to vacate in the Naval Yard. Neither his wife or his family – he has two daughters of 18 and 16 years of age and a son of 4 years of age – had any inkling of the horror that was soon to burst upon them. The murderer had gone home calmly, without betraying a sign of the deed that had been done, and he had breakfasted, and put a flower in his button hole.

When Constable Campbell came to the house the family was going on with its routine morning work, all heedless of the tragedy, and the officer did not tell them. “Frith,” said the officer, “you’d better come and take a walk with me; I want to talk to you.” The murderer understood. He put on his hat, buttoned his coat and then went out – Frith to a prison cell to await trial on the charge of murder.

As far as can be learned the tragedy is the result of a grievance which Frith believes he had against the man who lies dead on the slab in the morgue of the Naval hospital. For nine years they had been working together, and for nearly as long again Frith had been at work in the Naval Yard at Esquimalt, where he had his home in one of the houses belonging to the Admiralty. A few days ago he had been given notice to leave, and had already began to make arrangements for his departure. His furniture was being prepared for sale, and he was finishing out his time at work in the yard when he shot and killed the man whom he held was responsible for his discharge.

Whether he arranged to have the dead man go with him to the silent store room, where the deed was committed, does not appear. Possibly he did not – but it is a fact, as stated in his written confession, which was given after the superintendent of provincial police and other officers had warned him – that he went to Bailey shortly before or about 8 o’clock, and asked Bailey, who was the first-class storekeeper in charge of the Naval Yard, to get him some packing cases, and together they went to the store room – the oil store room in the sail loft building, where the packing cases are kept. Together they picked out a case, and Frith told the dead man that it would suit him, and they placed it outside the door.

When they had put the packing case outside, they returned inside and Frith locked the door. Bailey said, “Frith, what is the trouble between you and I?”

Frith replied: “There has been some undermining going on.”

Bailey then picked up a piece of board and said: “If you say I’ve been undermining you I’ll fix you.”

Words followed, and Bailey dropped the club and picked up a barrel stave. He did not strike.

After some words Bailey said he couldn’t stand it any longer and he was going to get satisfaction, and he turned around. As he did so Frith jerked his right hand behind and pulled his revolver from a pocket, and fired at the back of Bailey’s head. Bailey, who was then standing about five feet distant from the murderer fell dead, shot through the head. The murderer left the body lying on the floor, with the blood welling from the head, and he shut the door after him, turning the key in the lock. Then after walking to the dock and throwing the revolver with which [the] deed was committed into the sea, Frith went and told Constable Campbell that he had killed Bailey, after which he went to his house to breakfast, and remained there until he was arrested.

While the constable was taking the murderer to the city, the sergeant of marines had found the remains of the victim. They had searched several of the buildings without result, when one of the marines looked through the transom of the oil store room in which the tragedy had been committed, and he saw the dead body lying in a pool of blood on the floor. The marines broke in the locked door. They found the murdered man’s body lying stretched out, face downward, just as the unfortunate man had fallen. Blood was still oozing from a small wound at the back of his head and from a small wound in the forehead for the ball cartridge from the heavy bull-dog revolver had penetrated the skull, and had after entering the back of the head come out the forehead. The scene was a ghastly one for there was considerable blood.

The revolver which Frith had been carrying was a heavy bull-dog, with five chambers, carrying a heavy ball, and all the five chambers of the weapon had been loaded. The weapon still lies at the bottom of the harbor – and it is not thought that any steps will be taken to recover it.

The remains of Bailey were removed from the store room, where the tragedy took place, to the morgue of the Royal naval hospital at Esquimalt, and an inquest will be held by the coroner on Monday at 10 a.m. Then it is not improbable that further light will be shed on the causes with led to the murder of Bailey by Frith. It is well known at Esquimalt that the two men have not been on good terms, and Frith, who had been notified to leave the naval yard, blamed the dead man for having secured his dismissal. This was doubtless the cause which led to the murder.

Bailey, the victim of the tragedy, who succeeded Mr. Cassie, as store keeper at the naval yard two years ago when the former officer returned to England, was a man of about 35 years of age. He was a married man with a family of four children, and resided in a new house which had been recently completed on Esquimalt road, opposite the Head street switch of the Street Railway track. Mrs. Bailey has been in hysterics for the greater part of the time since the tragedy. The eldest child, a boy, is 11 years of age, and there are two other smaller boys, and a little girl.

Bailey was a prominent worker in religious and temperance work among the soldiers and sailors of Esquimalt, and was a lay preacher. He was treasurer of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home, which had recently been completed on the Esquimalt road under the superintendence of the Wesleyan chaplain, Rev. J.P. Hinks, who was a friend and co-worker of the dead man. He was also prominent in the Esquimalt lodge of A.F. & A.M., Frederick James Bailey being a past master of the Free Masons.

Frith, the man who is held with a charge of murder against him as a result of Bailey’s death, is a man of 40 or 45 years of age. He has been in charge of the coal wharf, lighters, etc. in connection with the coaling of the warships and storage of the Welsh coal brought from England. He was discharged about a week or two ago, as stated above. He was one of the crew of H.M.S. Rocket before joining the staff of the naval yard. He has a wife and family of three children, two girls and a boy. One of the girls is in Vancouver. Another girl was staying with Mr. and Mrs. Campbell at Esquimalt, while the arrangements to leave for Vancouver, where it was said Frith had secured work, had been completed. The family of Frith did not learn about the tragedy until the afternoon.

Frith is said to have been subject to apoplectic fits, and during last December a blood vessel burst in his head, as a result of which, his friends claim, he has been morbid and morose at times, and they are inclined to believe that he may have had an insane streak at times as a result, which may, or may not be partly responsible for the murder. He was sober at the time of the shocking affair, although he is known to have had two drinks during the morning previous to the tragedy.”

(Source: Daily Colonist, 28 June 1903, page 2, columns 3 & 4)

“Frith Executed at Provincial Jail

——————-

Death Sentence Carried Out Quickly and Without Slightest Hitch

——————

Condemned Man Met His fate With Unshaken Nerve and Coolness

——————

Alfred James Ernest Frith was hanged yesterday morning at two minutes past eight in the yard of the provincial jail for the murder of Frederick James Bailey, naval storekeeper at Esquimalt. Five months ago, early in the morning, he had asked Bailey to go to the store-house with him and, with a heavy bull-dog revolver held within a short distance of the back of his head, he shot down the naval storekeeper from behind – and yesterday morning he paid the penalty. With the same emotionless coolness and remarkable fortitude, the same deliberate nerve and self-possession and absence of bravado with has marked his attitude since he placed under arrest by the provincial police, he marched, without fear or discomposure, with military bearing, more upright than any man in that solemn procession from the caged gallery – the condemned cells – to the scaffold standing in the jail yard, and, erectly poised and cool as a soldier on parade, he strode along the sidewalk at the edge of the yard, and up the stairway to the platform, whence he had his last glimpse of the world. Cool, deliberate and without a sign of mental anguish, he walked on to the trap, threw back his shoulders firmer and drew himself into position. Then, stretching his neck to allow the hangman to slip the noose, he stood there, his remarkable nerve never deserting him for an instant, calmly and bravely awaiting the judgment of death demanded by the law to expiate his crime.

Frith had been a model prisoner, quiet and with few wants, making no efforts to avoid the consequences of his act of five months ago. He had continually avoided reference to the murder and had ever been as cool as he was in the hour of the climax of the tragedy. On Saturday last, when Sheriff Richards went to the jail in the afternoon and told him there was no reprieve for him, that the minister of justice had decided the law must take its course, and that his life repay that he had taken, he received the intelligence with the same marked fortitude.

“Well, I’m prepared to die,” he said when the sheriff told the dread news he brought. “I wish it had been tomorrow, though. It would have been better for my wife and family – but I’m prepared to die.” Then, whistling, he walked along the caged gallery until, after a few pacings of the short balcony, he turned to the guard – there was a man continually with him – and invited him to play a game of cards. Then, as he played, he told the guard, “Well, no one will ever know now why I did it. I did it, and I’m prepared to die.” Throughout his imprisonment he talked for the most part of commonplaces with the guards – each spent eight-hour watches with him – and did not desire reference to the tragedy.

He had a light breakfast, some eggs, toast and coffee, and as he ate, his spiritual advisor, Rev. Canon Paddon, sat with him. He asked for no favors, seeking no stimulant, no special dish for his last meal. The after breakfast, he talked with the clergyman, who comforted him with the cheering words of promise that the Scriptures contain, until five minutes to eight, when the Sheriff – the person of the law – came to claim him for the judgment of the law. Sheriff Richards entered the cage leading to his cell with the hangman, Radcliffe, and Frith met them on the gallery.

“The hour has arrived,” said the Sheriff.

Frith held out his hand, and as the Sheriff grasped it, he said, “Good-bye, Sheriff; I’m ready.”

Then began the march to the scaffold. Lead by Sheriff Richards, and with Warden John and the jail surgeon, Dr. J.S. Helmcken, following, came two justices of the peace, Messrs. R.B. McMicking and Thos. Shotbolt, then came Canon Paddon. Then, with two wardens standing immediately behind him, came the pinioned prisoner.

Canon Paddon read slowly and impressively the passages from the Church of England prayers. As the white cap was drawn over the head of the unfortunate man, “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,” repeated the clergyman, “I will fear no evil, for Thou art with me.” As he read the prisoner stood poised, as erect as ever, his body firm, his clasped hands still as those of a statue and his face betraying none of the feelings he may have felt. Then, as the clergyman concluded with the benediction, and with his open prayerbook before him was silent, the Sheriff raised his hand. The trap fell and the loose rope became taut with a jerk. There was no convulsion, no tremor, death having been instantaneous.

The body was left hanging, as demanded by law, for an hour. Dr. J.S. Helmcken, the jail surgeon, however, made an examination after the trap fell, and pronounced him dead.”

(Source: Daily Colonist, 28 November 1903, page 8, column 4)

Frederick James Bailey is buried in the Naval & Veterans Cemetery, Esquimalt, B.C.

Would you like to leave a comment or question about anything on this page?